Assessing Loom Investor Performance

Why MOIC doesn't tell the whole story

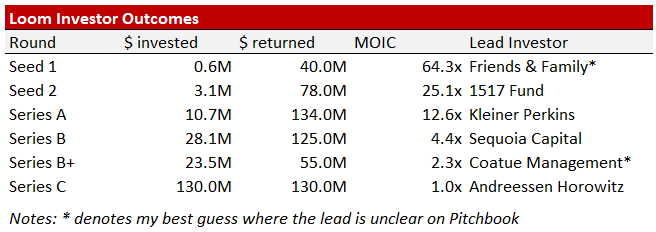

On Friday, San Francisco-based startup Loom – developer of “the easiest screen recorder you’ll ever use” – announced they had reached an agreement with Atlassian to be acquired for $975M. This represents a great outcome for almost everyone involved (founders, team, most investors) and is rightfully being celebrated as such across X and LinkedIn. Along with praise and congratulations, many are sharing summary statistics of the lead investors’ returns by round that look something like this:

While this summary is factually correct, I fear it may give a misleading impression in terms of which investor was most “successful” with their investment in Loom. For example, judging based just off MOIC one might conclude 1517 Fund’s Seed 2 investment was twice as successful as Kleiner Perkins’ Series A investment. Personally, I don’t think that’s quite the right takeaway. Let’s dive in.

Investors get compensated for Time and Risk, but MOIC1 expresses neither

Consider this very stylized example: Let’s say you have a dollar you’re looking to lend. If I offered to take your $1 and give you $2 back, would you accept my offer? It depends on when I’m paying you back. If I give you the $2 tomorrow, you’d likely say yes. But if I’m giving you the $2 in 10 years you’ll probably decline. Clearly, the timing of when you get paid back matters.

Additionally, your decision also depends on how risky you think it is to lend to me. If you think I’m good for the $2 you’re much more likely to lend to me than if you think I’ll take your money and run. Any time someone is lending or investing money they’re making (at least implicitly) an assessment of the risk they’re taking.

Unfortunately, because MOIC is a simple calculation of $ returned divided by $ invested there’s no way to express how long it took to realize that return or how risky the investment was. For me, that means it’s really difficult to judge which investment was the most “successful” based on MOIC alone.

IRR helps account for time differences

If we add the investment entry date to our table, we can calculate the IRR2 of each investment to compare them on a more time-weighted apples-to-apples basis.

With IRR included we’re starting to see a slightly different picture of performance. Even though 1517 Fund’s MOIC was more than two times greater than Kleiner Perkins’, Kleiner actually earned a higher IRR because they invested more than two years after 1517 Fund. In fact, Kleiner’s IRR is only slightly behind that of the Friends & Family round, despite their MOIC being just a fifth the magnitude.

While this view is helpful, even IRR tells us nothing about the risk investors assumed to earn these returns.

Accounting for risk is less straightforward, but potentially even more informative

Unlike with IRR, there’s no easy formula to effectively normalize for the risk early-stage venture investors take when making an investment. Intuitively we know a Seed stage investment is riskier than a Series B, but by how much? While there’s no perfect answer, we can observe success rates by investment stage and use them as a proxy for relative risk.

A longitudinal study published by CB Insights in 2018 showed that of 1119 tech startups that raised Seed funding in the US between 2008 and 2010, 335 would go on to raise a Series B and just 17 would eventually be valued or exited at over $1B. This implies a Seed investor has a (17 / 1119) = ~1.5% chance of investing in a Unicorn, whereas a Series B investor has a (17 / 335) = ~5% chance of doing so. If we use this CB Insights data for every round of investment in Loom, we can get a sense of the relative risk each investor assumed.

When we run this analysis and compute a relative risk score anchored to the Series C, some interesting insights emerge. For example, not only did Kleiner’s Series A yield a higher IRR than 1517 Fund’s Seed investment, but Kleiner achieved that return by taking less than half the risk. Essentially what I’m doing here is trying to assess the risk-adjusted returns of each investment, or the returns generated by each additional unit of risk assumed. Let’s make that more explicit by calculating risk vs. reward metrics:

For clarity, the MOIC Risk-Reward column = (MOIC / Relative risk) and the IRR Risk-Reward column = (IRR*100 / Relative risk).

Assessing investor performance

When we compare the performance of the MOIC Risk-Reward column across investors, it’s clear the Seed 1 investors achieved the best returns per unit of risk with a score of 9.9x. However, as we’ve already discussed MOIC doesn’t incorporate the required compensation for time, so let’s consider the IRR Risk-Reward column as well.

With IRR Risk-Reward we see that Sequoia’s Series B actually achieved the best performance with a score of 23.2x. Kleiner’s Series A is a close second, and even Coatue’s Series B+ performed better on this metric than either of the Seed rounds.

While I’m hesitant to say Coatue’s Series B+ was a better investment than 1517 Fund’s Seed – after all, 1517 Fund’s more than 10x better MOIC represents real money in the bank for LPs3 – it does raise the question of how we should think about investor performance and which metrics best illustrate that performance. If you forced me to choose, I would say Kleiner’s Series A with its 12.6x MOIC, 67.3% IRR, and 21.7x IRR Risk-Reward score looks the most attractive across the board.

What does this all mean?

By picking Kleiner Perkins as my “winner” despite them not having the best IRR Risk-Reward score I’m hopefully illustrating that no one metric can be used in isolation to assess performance. In fact, there’s not a single column in this table where Kleiner performed the best! Rather, I’m making the argument that many things matter in investing – cash on cash returns, time it takes to make those returns, risk assumed when investing – and therefore assessments of performance should consider each of these factors. Ultimately, my goal here is to pump the breaks slightly on assertions that the earliest stage investors always “did the best” when a startup has a big exit. Seed investors will definitionally have the best MOIC when there’s a Unicorn exit, but that doesn’t mean they were best compensated for the time and risk it took to generate those returns.

MOIC = Multiple on Invested Capital. If I invest $100 and get back $200, I have a 2.0x MOIC.

IRR = Internal Rate of Return. Think of it as the annualized rate of return you realize on an investment.

This is essentially the argument that “You can’t eat IRR”. I generally find this argument persuasive but don’t believe it should be used in isolation, which is why I incorporate MOIC as a factor but not the only factor to influence my view on performance.