Does Software Really Taste Like Chicken?

Why chicken may not be the right bird analogy.

A few years ago at an industry conference in New York, Vista Equity Partners founder Robert Smith famously said, “Software companies taste like chicken.” He went on to say, “They’re selling different products, but 80% of what they do is pretty much the same.” What did he mean by this? Is he right? Let’s dive in.

Software businesses tend to have similar economic models that can be analyzed quickly.

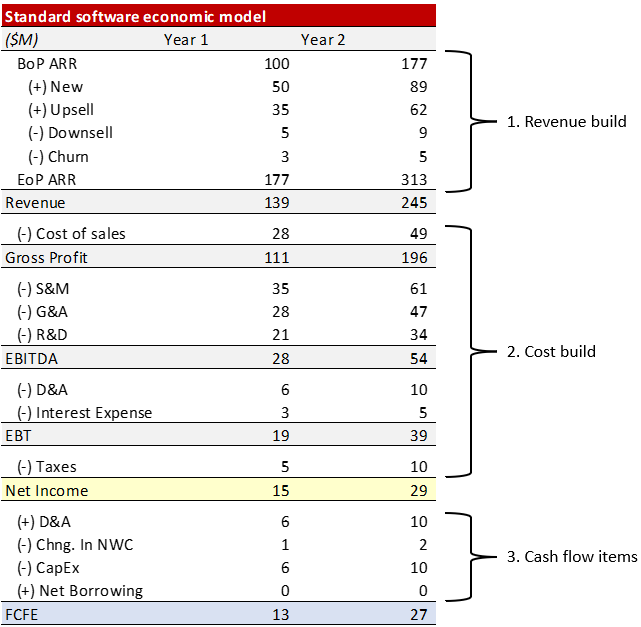

One of the first things you learn when you start a job as a software investor is the typical software company P&L. From the perspective of an equity investor, it’s comprised of three core building blocks:

Revenue build (typically an ARR bridge1)

Cost build

Cash flow items (important due to the deferred revenue benefit of subscription software2)

Each of these building blocks is itself comprised of a few sub-components, and when you put them all together you get a basic software economic model that looks like this:

Because software businesses tend to have such similar economic models, investors have developed heuristics that help them quickly assess the quality of these businesses. These include:

Gross dollar retention3

Net dollar retention4

Gross margin-adjusted CAC payback period5

And so on

Depending on the stage of growth other heuristics like revenue burn multiple6 or Rule of 407 may apply, but the basic premise is that at a high level a software business’ economic model can be quickly analyzed and understood by investors.

Standardized economic models can make assessing software businesses feel formulaic.

Software investors, especially private equity software investors, spend a lot of time analyzing businesses in excel. Given their standardized economic models many software businesses look alike on the spreadsheet, which can make assessing software businesses feel somewhat routine. You wrap your head around the problem the software is solving for customers, determine how big that opportunity is and how well the company is executing against it, and then quickly rip through the financials to decide whether you would be excited to invest. Of course, there is much more rigor applied before an investor actually writes a check, but for an initial screen this process is relatively straightforward. Many investors have even developed strict “buy boxes” whereby they only invest in software business that exhibit certain metrics (e.g., 90%+ gross dollar retention, 100%+ revenue growth, 12-months or less CAC payback period, etc.) that signal business quality.

However, outliers often break the rules.

When I was in private equity we had a preference for investing in businesses with best-in-class software metrics, but there were no hard-and-fast rules. It’s a good thing too, because one of the best software businesses I looked at as an Associate was a business that had less than 90% gross dollar retention (GDR). Despite this less than stellar metric, we were excited by the problem the business was solving and could see the superior value it was generating for its core customers, so we decided to lean in anyway. After digging through the data in more detail we learned that GDR was being dragged down by some legacy customers for whom the solution was not a good fit, but GDR for core customers was 95%+. This in fact was a phenomenal business anyone should be excited about investing in, but if we were dogmatic in our approach to screening investment opportunities we would have missed it.

Stories like this are hardly unique. Dropbox famously struggled to get their financial model to work before reorienting their go-to-market motion around a freemium to paid conversion funnel, and Hubspot experienced real retention challenges early on before they narrowed their focus on sales & marketing teams. Both businesses have since gone on to be worth $10B+, but investors who viewed them through the lens of consensus software metrics likely would have missed the opportunity to invest at attractive points along their growth journeys.

Similar software businesses can have very different operating models.

Take for example Snowflake and Databricks, two data infrastructure software solutions that sell cloud-native data storage and compute capabilities to enterprise customers. Despite increasingly competing head-to-head, the two businesses could not have more different go-to-market motions. Snowflake’s sales team follows a more traditional top-down sales motion, where account executives target Chief Data Officers who purchase the solution and then disseminate adoption enterprise wide. Databricks, on the other hand, has historically followed a more Product Led Growth (PLG) sales motion. Individual engineers download the open-source versions of Apache Spark or Delta Lake to start, then as adoption grows organically Databricks reps will route through users to establish a paid enterprise agreement. Both can be effective growth strategies – both Snowflake and Databricks are $30B+ businesses still growing 50%+ annually – but they require very different people, organizational cultures, and processes to get right.

And actually operating a software business is anything but easy.

Moving beyond an analyst’s perspective, actually building and running a software business is orders of magnitude more challenging than Smith’s statement would have you believe. For starters, building any business is hard. There’s operational roadblocks to tackle, people issues to sort out, key strategic questions to answer, roadmaps to plan for, and so much more. To gloss over these challenges, I think, is to minimize the herculean effort of entrepreneurship itself.

I believe these business challenges are only intensified within the context of software. Why? Software businesses have the unique feature of being comparatively quick businesses to start, and that means competitors are always just around the corner. Consider telecom as a counter example. If I wanted to start a telecom business to compete with AT&T or Verizon, I would need to invest billions in CapEx, spend years obtaining countless zoning approvals, and much more. However, if I wanted to start a software business (assuming I knew how to code) I could get up and running in a matter of weeks with just a few hundred dollars. These low entry barriers mean software executives are constantly looking over their shoulders, pressing to innovate and stay ahead of nascent competitors. Whereas an AT&T exec can afford the occasional misstep given their yearslong competitive lead, execs at software companies have no such luxury. Six months in software land is a long time, which is why even executives of scaled software businesses like Marc Benioff of Salesforce stress speed of innovation as the most important currency in software. This is doubly true for growth-stage businesses who don’t have the brand, distribution, or embedded customer base advantages of Salesforce. To get and stay ahead, you need to build faster than your competition. As a result, software leaders face consistent and heightened pressure to not only innovate quickly, but also to get it right every time.

So does software really taste like chicken?

I can certainly see where Smith is coming from. Software businesses have consistent and predictable economic models which make them comparatively easy to understand and underwrite. From an investor’s perspective this may make them feel homogenous, but the devil is often in the details. Not all great software businesses will fit within an investor’s “buy box” when it’s time to make the investment, and even software businesses that sell similar products can have very different operating models. Plus while Smith didn’t explicitly say operating a software business is easy, I fear painting them with such a broad-brush statement minimizes the difficulty of a software founder’s entrepreneurial journey.

So while I deeply respect Smith’s investing prowess, I disagree that software tastes like chicken. If we want to stay in the bird family with this analogy, I’d say software companies are more like ducks: They appear calm on the surface, but are each uniquely paddling like hell underneath.

1. ARR Bridge – ARR or Annual Recurring Revenue is a point-in-time measurement of how much revenue a business has contracted to earn from its customers over the next 12 months. It is a metric specific to software because software businesses tend to sign customers to annual (or multi-year) contracts and bill them in advance, which makes the revenue more predictable. The amount of ARR a business has signed up will vary throughout the year based on how many new customers are added, how many existing customers churn off the platform, and any net increases or decreases in existing customer spend. To determine the health and trajectory of a software business investors like to lay these dynamics out in an ARR bridge, which is commonly expressed as the walk from Beginning of Period (BoP) ARR to End of Period (EoP) ARR laid out above.

2. Deferred Revenue – Software businesses bill for and get paid for a whole year of services upfront, but can’t recognize all that revenue until the customer actually uses the software each month (due to GAAP accounting standards). For example, if on January 1st a customer pays $120 for a year’s subscription to a software product, that company can only recognize $10 of revenue for January. The remaining cash ($110 in this case) that customers have paid a software vendor is called deferred revenue and is a source of cash for the business.

3-7. Software Metrics – For more detail on common software metrics and benchmarks for good vs. great I would recommend the Andreessen Horowitz Growth team’s Guide to Growth Metrics.

This was fun to read

Very interesting, Jeff! I recently wrote a piece on how virtually every company is converging to X-as-a-Service and they're definitely all various flavors of the same core SaaS model.

Is Every Company Becoming a Software Business?

https://brandanatomy101.substack.com/p/is-every-company-becoming-a-software